Helpful Tips

IS OUR GUT FLORA WORKING FOR OR AGAINST US?

( Quoting Dr. Bert Herring, Fast 5)

In the normal human gut, a lot of bacteria live in the large intestine (called intestinal flora, microbiota or gut microbiome). There are so many bacteria living in your intestine that they outnumber your own cells. These bacteria may affect digestion, health and appetite. The microbiome is a very complex environment, and figuring out what does what is difficult. There are contradictions, controversies and disagreements, so actionable findings are still foggy.

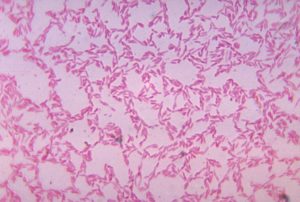

Bacteroides bacteria

People with some severe diseases such as ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease have benefited from treatments aimed at changing the bacterial population in the gut. The bacteria have been found to affect energy absorption in mice, and studies in humans are underway.

It’s not easy to change the bacteria in your gut. If you were born in the usual way, your gut bacteria was seeded with the bacteria present in your mom’s birth canal. If you were born by Cesarean section (C-section), the seeding is more random. Bacteria that were commonly found in the intestine decades ago are less common now, so scientists are wondering if the change is related to the obesity epidemic.

Some species of bacteria, such as Akkermansia, have been associated with leanness. It’s important to note that this is an association, not a a cause-effect link. That means that scientists have found that Akkermansia tends to be more common in lean people than in people with surplus fat, but it has not been proven that the lean people are leaner because they have more Akkermansia in their intestine.

For serious illnesses (including extreme obesity), researchers are working with stool transplant techniques. These techniques aim to wipe out existing bacteria with antibiotics and replace them with bacteria from a lean, healthy person who has been carefully screened for undesirable viruses like hepatitis, HIV, and herpes. Various methods are being used, but one way or another, they put someone else’s poop into the gut from above or below or both, using a tube, colonoscope, enema, etc.

Short of a poop transplant, there are alternatives that may help. Keep in mind that shifting the established bacteria population takes time. It’s a sluggish process, because the existing bacteria make it hard for others to grow—it’s sort of like planting a garden in the middle of an existing forest without clearing any trees. Results, if any, may be so gradual that they’re difficult to see. To conduct a study of one, you can see what’s currently in your gut using a microbiome survey such as Ubiome’s “Time Lapse Explorer” ($199, no affiliation), repeating the test after 3-6 months of “gardening” efforts directed at shifting your intestinal bacteria population toward a leaner mix.

Understanding Your Results

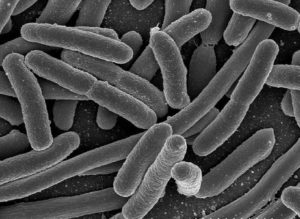

E. coli, a common intestinal bacterium

Test results from Ubiome are difficult to interpret. It helps to know that a phylum (plural: phyla) is a giant category that includes many smaller categories, including genera (singular: genus) and species. You’ll see counts for 80 or so different types of bacteria. Greater diversity (more species present) is generally a good thing. If your gardening efforts are working, you’ll see an increase in the Bacteroidetes phylum, a drop in the Firmicutes phylum and an increase in the Akkermansia genus. It is entirely possible that you may see a change but still have no easier time losing weight. Bifiodbacterium is in the phylum Actinobacteria. Firmicutes includes Lactobacillus.

Your Gardening Tools

Your options for changing your intestinal flora come in five forms: probiotics, prebiotics, fiber, exercise and fasting. Probiotics are bacteria sources you eat; the bacteria have to survive the digestive process, including stomach acid, to be able to grow in the intestine. Prebiotics are foods you eat that encourage the growth of desirable bacteria.

Probiotics

Probiotics attempt to seed growth of desirable species. Probiotics include things like yogurt with active cultures or probiotic supplements. The bacteria in them vary, and there’s not yet any evidence that strongly favors one over another. Most of the bacteria you take by mouth get killed by stomach acid and digestive enzymes, but some survive. There are not yet any probiotics with Akkermansia bacteria. Some have Lactobacillus, which is better than some undesirable bacteria but I’ve seen nothing that makes it desirable from a weight-loss perspective.

Prebiotics

Some prebiotics have been shown to increase Bacteriodetes and Akkermansia in mice. There’s no guarantee that they’ll work as well in humans, and even if they were shown to work in some humans, that doesn’t mean they’ll work for you. That’s why treating this as a study of one (yourself) is important. I favor using the raw item rather than extracts, because it’s almost impossible to know what treatments the extract has been through that might inactivate the helpful content. Most of these supply a class of chemical called polyphenols that increase the mucin in the gut lining that supports Akkermansia growth.

- Cranberries

- Cherries

- Grapes

- Pomegranates

Fructooligosaccharides (FOSs), which are not digested by our enzymes, can support Bacterioidetes but don’t appear to help Akkermansia. FOSs can be found in:

- asparagus

- bananas

- blue agave

- garlic

- Jerusalem artichoke

- jícama

- leeks

- onions

Bacterioidetes tends to do best with a low-fat diet with complex carbohydrate sources such as beans and lentils. Diversity in your diet is important, too, so try different plants often.

Avoid: artificial sweeteners, emulsifiers (carrageenan, mono- and diglycerides, lecithin)

Fiber

Fiber helps keep your gut moving. Prompt movement may help protect some bacteria that you ingest, supporting the probiotics you may use and the diversity of your intestinal flora. The recommended minimum for fiber is 30 grams/day.

Exercise

There are many good reasons to exercise. Now you have one more: exercise can increase Akkermansia populations.

Fasting

Every-other-day fasting has had beneficial effects on the gut microbiota in mice. It may have a similar effect in humans. Indeed, many of the benefits seen with intermittent fasting may be related to its effects on intestinal flora.

What to Watch

How will you know if changing your diet is changing your intestinal flora? A DNA-based test like Ubiome may be the best way to monitor your flora, but you may see other clues that things are changing:

- You may have more gas, especially at first

- Your stool (poop) may look or smell different from your usual

- Your weight loss efforts may be more successful

- You may experience fewer symptoms of inflammation (pain, swelling) if you have any, such as arthritis

- Your appetite may change or be reduced

- If you tend to feel bloated after meals, you may notice less of it